Construction Incident Reporting: Types, Steps & Templates

In construction, incident reporting is essential for ensuring worker safety and meeting legal compliance.

According to OSHA, over 20% of all workplace fatalities occur in the construction industry, making it one of the most dangerous sectors. Without effective reporting, companies risk severe penalties, increased liability, and, most importantly, further harm to their workers.

This guide breaks down the steps involved in incident documentation, outlines the requirements specific to construction sites, and explains how occurrence tracking systems and software can streamline the process. This guide also covers the legal implications of failing to report incidents and shos how incident data can drive improvements in safety culture.

By the end of this article, you will understand how to implement a robust reporting system that helps reduce accidents, ensures compliance, and improves overall safety on your site.

What is Incident Reporting?

Incident reporting refers to documenting events that cause or have the potential to cause harm to people, property, or the environment on a construction site. These reports capture critical details, such as the who, what, where, and when, along with immediate actions and root causes.

Type of Incidents Reporting

Incident reporting is a critical tool not only for regulatory compliance but also for learning and continuous safety improvement. By categorizing events, businesses can identify specific hazard trends and implement targeted preventive measures. The following are the key types of incidents that must be documented on a construction site:

1. Safety Incidents (Accidents)

These are unplanned events that result in injury, illness, or property damage. In the construction industry, these incidents are often categorized by the "Fatal Four" (falls, struck-by, electrocutions, and caught-in/between), which tragically account for the majority of construction fatalities. Comprehensive reporting is essential for understanding the root causes of these accidents and implementing effective corrective actions.

2. Near Misses

A near miss is a potential hazard or incident in which no property was damaged and no personal injury was sustained, but where, given a slight shift in time or position, damage or injury could have occurred. Reporting these "close calls" is crucial for proactive risk mitigation, as they are often precursors to more serious accidents. Analyzing near-miss data allows companies to address systemic safety weaknesses before a major incident occurs.

3. Equipment & Vehicle Incidents

This category covers malfunctions, breakdowns, or operational errors involving heavy machinery, tools, or site vehicles that pose a safety risk or cause project delays. Examples include crane failures, scaffold collapses, or accidents involving forklifts and dump trucks. Detailed reporting helps track maintenance needs and identify training gaps for equipment operators.

4. Occupational Health Incidents

These events involve exposure to long-term or acute health hazards on the construction site. This includes exposure to harmful substances like silica dust or asbestos, excessive noise leading to hearing loss, or acute conditions such as heat stress and exhaustion from extreme weather. Documenting these incidents ensures that worker health is protected and appropriate control measures are put in place.

5. Environmental Events

Environmental events are incidents that result in the unauthorized release of pollutants or damage to the surrounding environment. This covers a range of issues from fuel or chemical spills and soil contamination to improper waste disposal and violations of local environmental regulations. Reporting these incidents is vital for regulatory compliance and demonstrating a commitment to environmental stewardship.

Incident documentation is a tool not only for compliance but for learning, as it allows businesses to identify hazards before they become major issues.

Essential Steps for Incident Reporting

To ensure accuracy and compliance, every construction site should follow these five steps immediately after an incident occurs:

- Secure the Scene and Provide Aid: The first priority is the safety of personnel. Clear the area to prevent further accidents and provide immediate first aid or emergency medical services to any injured workers.

- Notify Supervisors and Authorities: Report the incident to the site supervisor immediately. If the incident involves a fatality or serious injury, you must adhere to mandatory timeframes for notifying regulatory bodies like OSHA.

- Gather Evidence and Witness Statements: Collect data while the details are fresh. Take photos of the scene, equipment, and any environmental factors. Interview witnesses and record their accounts of the sequence of events.

- Complete the Incident Report: Use a standardized template to document all findings. Ensure you include the exact location, time, and personnel involved. Digital tools can help standardize this data across multiple sites.

- Conduct a Root Cause Analysis: Identify why the incident happened, not just what happened. Determine if the cause was a lack of training, equipment failure, or poor site conditions, and implement corrective actions to prevent recurrence.

The Importance of Incident Reporting in Construction

Incident reporting is not merely a bureaucratic task; it is a fundamental component of a proactive safety strategy. The importance of thorough documentation can be broken down into three core areas:

- Ensuring Regulatory Compliance: Reporting is non-negotiable for meeting legal requirements set by bodies like OSHA and HSE. Failure to report serious incidents within strict timeframes (e.g., 8 hours for fatalities) results in severe fines, legal action, and increased liability.

- Driving Incident Prevention: Reports provide the essential data for root cause analysis, allowing companies to identify and eliminate recurring safety hazards. This data-driven approach is key to preventing the most common and fatal construction accidents, such as those categorized in the "Fatal Four."

- Fostering a Strong Safety Culture: Encouraging workers to report all incidents, including minor events and near misses, without fear of punishment creates a transparent environment. This open dialogue ensures that management and workers alike take responsibility for safety, leading to continuous improvement and the early detection of systemic issues.

Key Metrics and KPIs in Incident Reporting

Below are the core KPIs, their formulas, and how they inform safety management practices.

1. Incident Frequency Rate (IFR)

Incident Frequency Rate (IFR) is a critical KPI for tracking the frequency of incidents on a construction site, normalized against the number of hours worked. It is used to measure safety performance over time and evaluate whether preventive measures are effective.

Formula:

IFR = (Number of Incidents × 1,000,000) / Total Work Hours

2. Days Lost to Injury

The Days Lost to Injury metric tracks the total number of workdays lost due to injuries on-site. This KPI helps companies assess the severity of incidents and how they impact overall project timelines and labor costs.

Formula:

Days Lost to Injury = Sum(Days off due to Injury per Worker)

3. Incident Severity

Incident Severity categorizes incidents based on their impact on workers, operations, and equipment. This KPI helps prioritize resources and actions based on the seriousness of incidents.

Formula:

While incident severity is typically categorized as Minor, Major, or Critical, it can be quantified through a weighted scoring system, such as:

Severity Score = (Minor Incidents × 1) + (Major Incidents × 3) + (Critical Incidents × 5)

Where:

- Minor Incidents: Events causing little disruption or harm.

- Major Incidents: Accidents that cause moderate injuries or damage to equipment.

- Critical Incidents: Severe accidents with significant injuries, fatalities, or substantial property damage.

4. Lost Time Incident Rate (LTIR)

Lost Time Incident Rate (LTIR) tracks the number of lost time incidents (LTI), where a worker is unable to return to work after an injury per 1 million hours worked. LTIR is used to evaluate the severity and overall risk level of a site.

Formula:

LTIR = (Number of LTIs × 1,000,000) / Total Work Hours

Construction Incident Reporting Template

1. Incident Identification

- Incident Number: ___________________

- Date of Incident: ___________________

- Time of Incident: ___________________

- Location of Incident: ___________________

2. Incident Type (Check all that apply)

- Workplace Accident

- Near Miss

- Equipment Failure

- Health Incident (e.g., exposure to hazardous materials, extreme weather)

- Environmental Event (e.g., spill, contamination)

- Other: _______________________

3. Personnel Involved

- Name(s) of Injured Worker(s): ____________________________________

- Job Title(s) of Worker(s): _______________________________________

- Supervisor’s Name: ___________________________________________

- Witnesses:

- Name: _______________________ Job Title: _______________________

- Name: _______________________ Job Title: _______________________

- Name: _______________________ Job Title: _______________________

4. Description of the Incident

(Provide a detailed description of what happened, including the sequence of events, contributing factors, and immediate actions taken.)

- Incident Description:

5. Injury/Property Damage

- Nature of Injury (if applicable):

[ ] Minor (e.g., cuts, bruises)

[ ] Major (e.g., fractures, sprains)

[ ] Fatal (e.g., death)

[ ] No Injury

If injury occurred, provide details: ____________________________

If property damage occurred, describe: _______________________

6. Immediate Actions Taken

- First aid provided

- Incident contained (e.g., spill, fire)

- Emergency response activated

- Worker sent to medical facility

- Equipment shutdown

- Other: _______________________________________________________

7. Root Cause Analysis

- Immediate Cause: (What directly led to the incident?)

- Contributing Factors: (What were the underlying causes? Lack of training, poor equipment maintenance, etc.)

- Corrective Action(s) Taken:

8. Corrective and Preventative Actions

(What will be done to prevent the incident from recurring? Include actions such as training, policy updates, equipment repairs, etc.)

- Action(s) Taken:

- Follow-up Actions:

9. Reporting and Notifications

- Supervisor Notified:

Name: _______________________

Time Notified: ___________________ - Regulatory Body Notified (if required):

[ ] OSHA

[ ] Local Health and Safety Authorities

[ ] Other: _______________________

10. Incident Report Submitted By

- Name: _______________________________________

- Job Title: ____________________________________

- Date: _______________________________________

11. Additional Notes

(Use this space to add any further observations or relevant information related to the incident, including photos or sketches.)

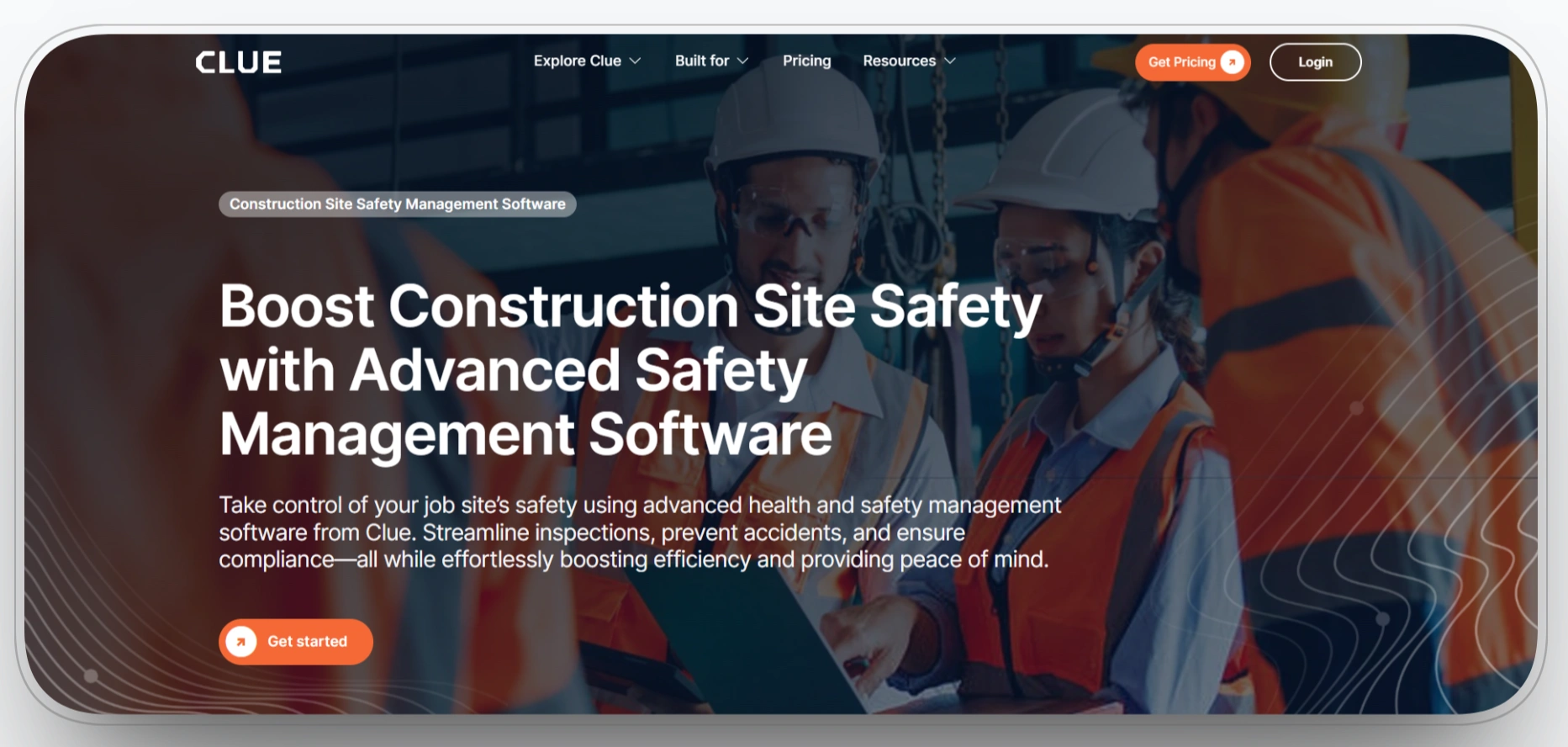

Advanced Incident Reporting and Safety Management with Clue

Clue is a construction maintenance management platform focused on safety management, inspections, compliance, and operational reporting within heavy civil and equipment centric environments.

Its core capabilities enable construction firms to capture, document, and act on safety‑related data; including incidents, near‑misses, equipment issues, and compliance checks in a digital, structured format.

1. Safety Management Core

Clue’s safety management software is designed to help teams:

- Prevent accidents through structured safety workflows and real‑time monitoring of hazards and conditions.

- Ensure compliance by automating safety checks, maintaining accurate records, and generating audit‑ready reports.

- Report near misses and unsafe conditions in a digital, searchable system accessible from any job site.

- Track safety issues consistently across multiple sites from a single dashboard.

Incident reports, once logged through mobile or web interfaces, become part of the structured safety dataset that is stored and used for trend analysis and compliance documentation.

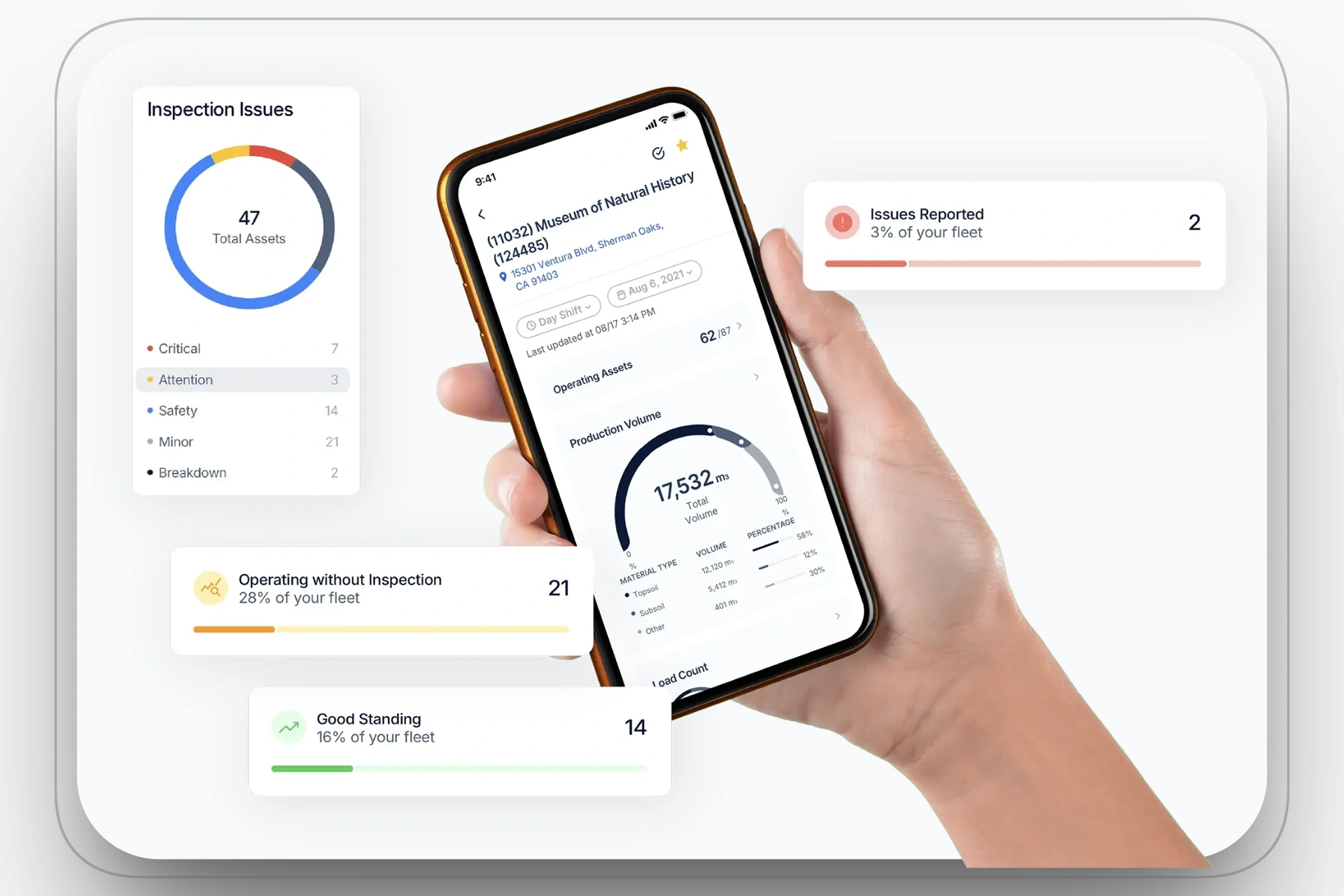

2. Digital Capture of Incidents and Site Issues

Clue’s software provides a mobile‑friendly environment for field personnel to report safety issues and incidents as they occur:

- Mobile and Web Reporting: Workers can record safety issues such as equipment failures or unsafe conditions directly in the iOS/Android app during inspections.

- Visual Documentation: Photos, videos, and location coordinates can be attached to reports, improving accuracy and evidentiary value.

- Near‑Miss Reporting: The platform specifically supports proactive reporting of near misses, allowing teams to document hazards before they turn into actual incidents.

This replaces paper forms and ensures that safety issues are documented immediately and consistently across projects.

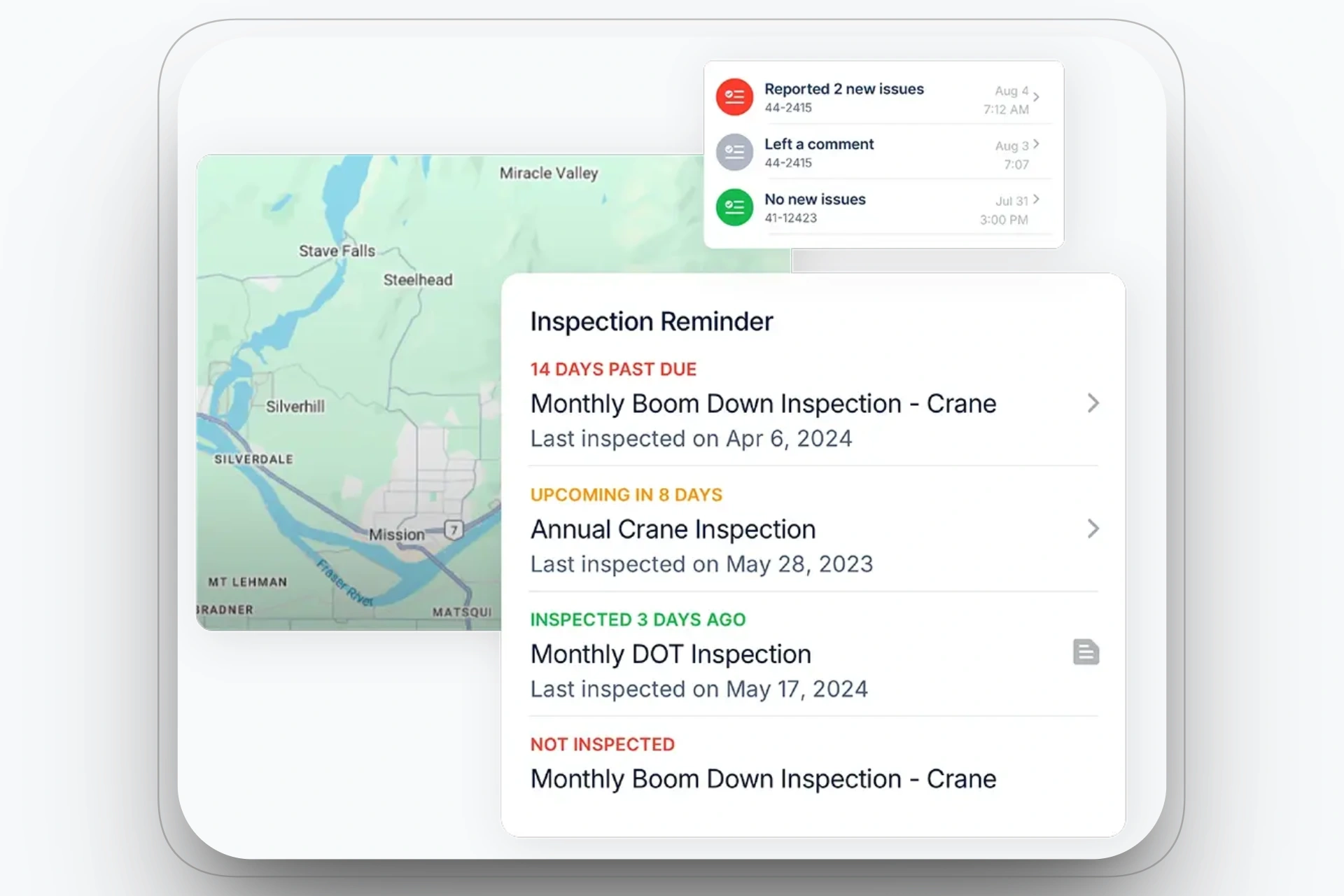

3. Inspection‑Linked Safety Reporting

Incident reporting in Clue is tightly associated with its inspection workflows, where safety issues are often first identified:

- Custom Inspection Templates: Users create inspection checklists that match regulatory or internal safety standards.

- One‑Click Issue Logging: When an inspection reveals a problem, it can be logged as an incident or issue with a single tap, reducing data loss.

- Integration with Maintenance: Inspection findings can be converted directly into maintenance requests or work orders to ensure corrective action is tracked and completed.

This structure ensures that incidents and hazards identified during inspections feed directly into the safety reporting pipeline rather than remain siloed in ad‑hoc notes.

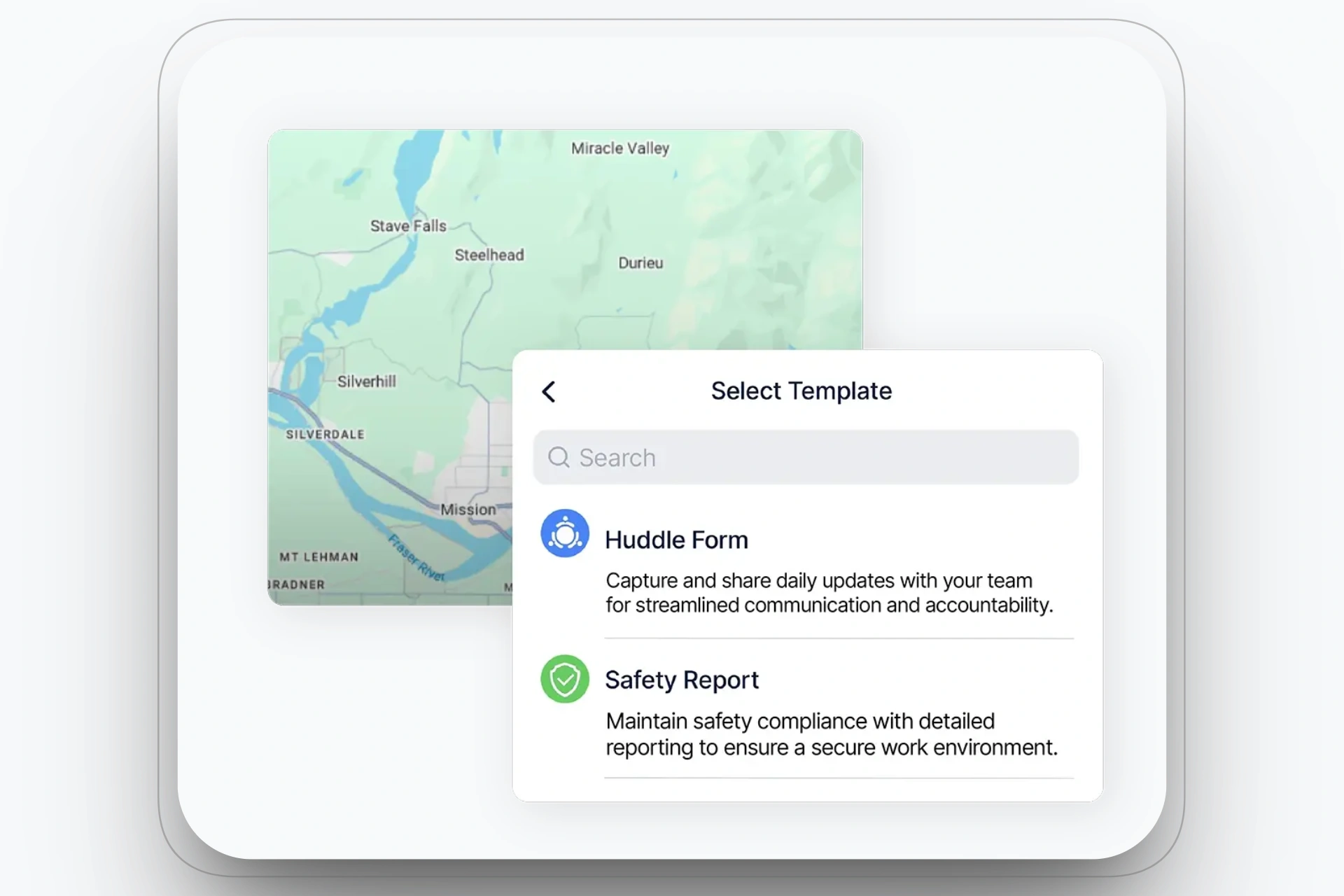

4. Toolbox Talks for Safety Engagement

Clue includes a dedicated Toolbox Talks capability that enhances safety communication and supports incident prevention by reinforcing safety awareness around known hazards:

- Automated Scheduling: Safety meetings (toolbox talks) can be scheduled and dispatched automatically, helping ensure consistent delivery without manual planning.

- Customizable Templates: Talks can be tailored to site‑specific hazards or project needs, enhancing relevance and engagement.

- Real‑Time Attendance Tracking: Supervisors can monitor who participated in safety discussions as they occur, improving accountability and compliance.

- Centralized Record Keeping: All safety meeting records, including talk topics and attendance are stored in one location for audits and reviews.

- Integration with Safety Data: Toolbox talk records can be linked to safety issues and maintenance workflows, ensuring lessons from incidents are reinforced through safety communication.

This capability supports cultural reinforcement of safety practices and ensures that knowledge derived from incident reports is communicated back to crews through toolbox talks, pre-task briefings, and updated jobsite procedures.

5. Centralized Data for Compliance and Reporting

All incident and issue reports are stored in a centralized database, allowing construction teams to generate organized records for compliance and audit purposes:

- One‑Click Report Generation: Clue can generate inspection and issue reports instantly, making documentation audit‑ready.

- Export Capability: Reports can be exported for sharing with regulators, clients, or safety leadership.

- Consistent Record‑Keeping: Safety data is preserved in a structured format rather than fragmented in spreadsheets or loose paper notes.

This centralization supports consistent incident documentation across multiple sites and time periods, helping with both internal safety analysis and external compliance demonstration.

Best Practices for Incident Reporting in High-Risk Construction Areas

Construction projects such as high-rise buildings or those involving hazardous materials require tailored approaches to incident tracking due to the higher likelihood of serious incidents. Best practices include:

1. High-Risk Incident Protocols

For high-risk areas, companies should have specialized reporting protocols in place. These may include specific forms for dealing with incidents involving electrical hazards, falling objects, or chemical spills.

2. Specialized Employee Training

Employees working in high-risk zones should receive specialized safety training relevant to the specific hazards of their tasks. These training programs should also include detailed instructions on incident intake and reporting procedures.

3. Cross-Department Collaboration

High-risk construction sites often require collaboration between different departments such as engineering, safety, and operations. This ensures that the incident reports are reviewed from all angles to prevent recurrence.

Legal Considerations and OSHA Compliance for Incident Reporting

Failure to comply with federal and state reporting requirements or mishandling an incident report can lead to severe legal and financial ramifications. Key considerations include:

1. OSHA Recordkeeping and Worker’s Compensation

Accurate and timely incident intake is essential for maintaining OSHA 300 Logs and ensuring workers receive appropriate compensation. Proper documentation prevents the delays and disputes that often arise when reporting fails to meet OSHA’s strict recordkeeping standards.

2. Liability and OSHA Citations

Companies face significant liability if they fail to report serious incidents, such as fatalities or hospitalizations, within OSHA’s mandatory timeframes (8 and 24 hours, respectively). Non-compliance can result in heavy OSHA citations, costly lawsuits, and long-term reputational damage.

3. Insurance and OSHA Incident Rates

Incident reports directly influence a company’s insurance premiums. Insurers closely monitor OSHA Incident Rates, such as the Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR); accurate reporting helps demonstrate a commitment to safety, preventing unnecessary premium increases and inflated claims.

Conclusion

In construction, incident reporting is a crucial aspect of maintaining a safe work environment. Whether through traditional methods or modern incident intake software, the goal is always the same: prevent future incidents and protect workers.

By adopting best practices, embracing technology, and ensuring compliance, construction companies can make significant strides toward achieving zero incidents and creating a sustainable safety culture.

FAQs

Who must report an incident on a construction site?

In many regulatory frameworks, the responsible person for reporting is not just the injured worker but the party in control of the construction site. For example, if a self‑employed subcontractor is injured but another contractor controls the site, that controlling contractor is responsible for reporting the incident.

Are near‑misses formally reportable even if no injury occurs?

Yes. A near miss is an unplanned event that could have led to injury or damage but did not. While some regulatory bodies focus on actual harm, many safety management standards treat near misses as reportable because they indicate hazards that require corrective action to prevent future incidents.

Can incident reports include multimedia evidence?

Yes, modern incident reporting tools allow the inclusion of photos, videos, timestamps, and GPS data to enhance accuracy and support investigations.

What incidents must be reported to OSHA and when?

OSHA requires reporting fatalities within 8 hours and inpatient hospitalizations, amputations, or eye loss within 24 hours.

What should a comprehensive construction incident report include?

Include the location, date, time, task, involved personnel, witnesses, incident sequence, immediate actions, injury or damage details, and corrective actions with assigned owners and deadlines.

What qualifies as a near miss and why should it be reported?

A near miss is an unplanned event that could have caused injury or damage but did not actually result in harm. Reporting near misses helps catch hazards early and prevents future accidents.

What details must be provided when reporting an incident to OSHA?

When reporting to OSHA, employers must include the business name, employee(s) involved, date and time, location, and a brief description of what happened.

Transform Your Equipment Management

.webp)

%20What%20It%20Is%20and%20What%20to%20Include.webp)