8 TPM Pillars: A Simple Guide to Heavy Equipment Maintenance

If you manage heavy construction equipment, you already know the painful truth: downtime rarely stays “small.” A delayed start on an excavator turns into idle trucks, missed compaction windows, rushed finishing, and a crew that spends the day recovering instead of producing.

That’s exactly the problem Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) was designed to solve: create a repeatable system that reduces unplanned stops and makes equipment performance predictable, not hopeful.

This is a jobsite-first guide to the 8 TPM Pillars: how they work, what “good” looks like for heavy fleets (excavators, dozers, loaders, graders, rollers, telehandlers, cranes), and how to implement them without turning your shop into a paperwork factory.

What is TPM for heavy equipment?

Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) is a reliability operating system that keeps heavy equipment (excavators, dozers, loaders, cranes, compactors) ready, running at planned pace, producing spec work first pass, and safe to operate by combining operator-led care, planned maintenance, problem elimination, training, and admin workflow discipline.

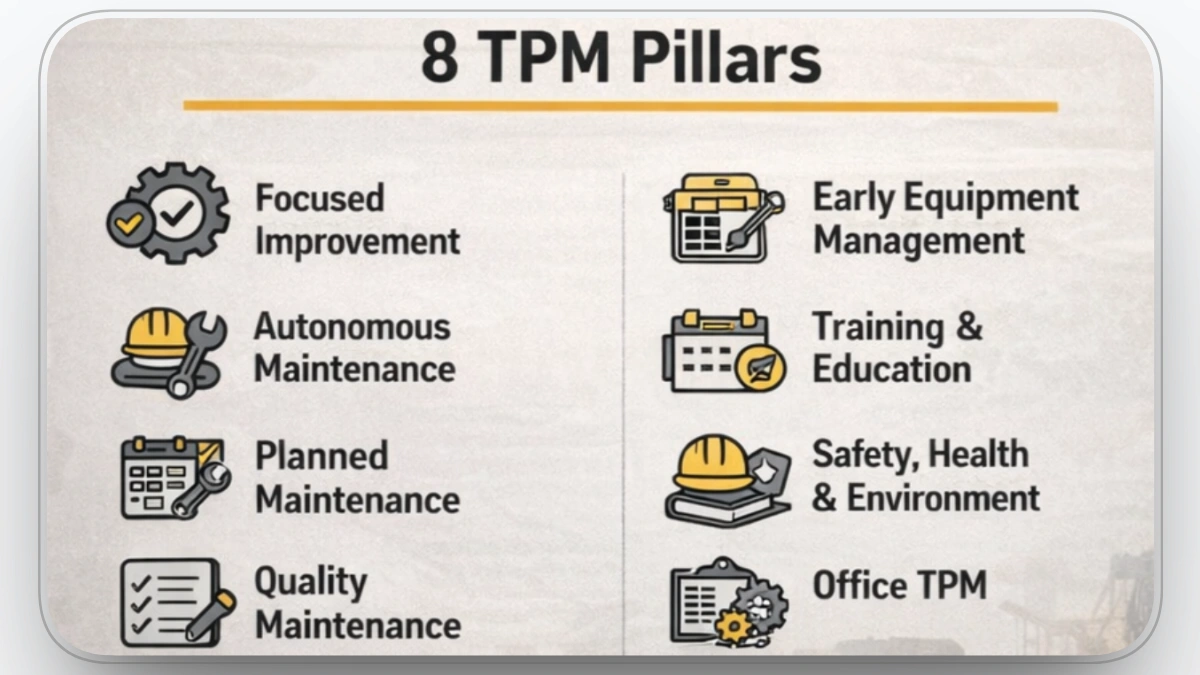

What are the 8 TPM Pillars?

The eight pillars of TPM form the foundation of an effective maintenance system. Each pillar targets a specific area of equipment reliability and operational discipline, and together they reduce the big losses that hit production: breakdowns, minor stops, slow running, quality defects, and safety incidents.

- Focused Improvement: eliminate chronic losses (repeat failures, nuisance derates, recurring downtime patterns).

- Autonomous Maintenance: operator-led daily care to detect abnormalities early (clean/inspect/lube/report).

- Planned Maintenance: PM + condition-based work done deliberately with parts/labor ready.

- Quality Maintenance: maintain machine conditions required to hit spec first pass (no rework).

- Early Equipment Management: design reliability into new purchases/rebuilds (serviceability, common parts, setup).

- Training & Education: raise operator detection skills + technician diagnosis/repair quality.

- Safety, Health & Environment: remove condition-based hazards before they become incidents.

- Office TPM: remove administrative “waiting downtime” (parts, approvals, work orders, dispatch handoffs).

In construction terms, these pillars eliminate the “hidden leaks” in production capacity: breakdowns, slow running, rework, safety exposure, and administrative waiting.

TPM in Jobsite Language

Manufacturing teams often use OEE. Heavy construction can translate the same logic into four questions your superintendent, dispatcher, and shop lead can agree on:

1) Is the machine ready when the plan says it should be?

“Ready” means it starts on time, passes basic checks, and is physically present where it is scheduled. A dozer that starts at 9:00 a.m. is not “available,” even if it runs perfectly afterward.

2) Does it run at the pace the plan assumed?

A loader that is “operational” but overheats, derates, or needs constant rework by the operator is quietly eating your production curve.

3) Does it produce spec work the first time?

Over-excavation, grade drift, compaction failures, and lift-plan rework are not “quality issues.” They are downtime in disguise.

4) Is it safe to operate today?

In TPM, safety is not a separate initiative, it is part of the same objective (stable operations, zero surprises).

TPM ownership on a jobsite (who does what)

TPM only works when ownership is clear. Use this simple split:

- Operators: daily checks, abnormality reporting, basic care (clean/inspect/grease-as-assigned).

- Foreman/Superintendent: enforce triage rules, protect downtime windows, verify checks happen.

- Dispatcher/Fleet coordinator: “ready on time” planning, swaps, and location readiness.

- Shop lead/Planner: weekly plan, scope definition, kitting, scheduling, backlog control.

- Technicians: diagnosis, planned repairs, root-cause elimination, quality of fix.

- Parts/Procurement: reorder points, frequent-stopper kits, vendor lead-time tracking.

- Fleet manager: KPI review, standards, audit cadence, escalation when the system slips.

Why Heavy Equipment TPM Needs a Construction-Specific Approach

TPM came from plant environments, but construction adds three realities TPM must be built to handle:

- Harsh Variability: Dust, Mud, Water Intrusion, Vibration, Temperature Swings.

- Utilization Volatility: High Idle Time, Short-Haul Cycles, Multi-Shift Surges, Frequent Mobilization.

- Human Variability: Different Operator Styles, Turnover, Mixed Training, Changing Site Leadership.

A strong TPM program doesn’t fight variability with more paperwork. It wins by creating standards that still work when the site is chaotic.

Benefits of TPM for Heavy Construction Equipment

TPM is not a “maintenance initiative.” It is an operating discipline that makes equipment performance predictable instead of hopeful. When the pillars are executed with real routines and real follow through, the benefits show up in the same six areas every jobsite fights daily.

Fewer start of shift surprises

More machines ready when the plan says they should be ready. That means fewer delayed starts, fewer emergency swaps, and less time spent reshuffling crews because one unit did not show.

Less slow running that quietly kills production

TPM does not just reduce breakdowns. It reduces the soft losses that drain output, derates, overheating recoveries, constant small stops, and operator workarounds that stretch cycle times all day.

More first pass quality and less rework

When equipment stays inside capability limits, you get fewer grade corrections, fewer compaction do overs, fewer over excavation fixes, and fewer rushed closeout days caused by preventable machine condition issues.

Lower maintenance cost over time through fewer repeat problems

The win is not “we repaired it.” The win is “that failure pattern stopped coming back.” TPM shifts work toward planned interventions, reduces repeat repairs, and improves parts readiness so labor hours produce results instead of comebacks.

Stronger safety stability

A stable machine is a safer machine. TPM tightens the link between condition and safety by pushing defect discovery earlier and driving faster closure on safety critical issues before they become incidents.

Better team ownership and less firefighting fatigue

When operators know what to look for and technicians get planned windows with parts ready, the whole system becomes calmer. Less chaos, fewer urgent calls, and fewer days where the shop is reacting to whatever broke loudest.

How to Roll out TPM Without Burning out Your Team

A construction fleet can make real progress in 90 days if it sequences work correctly:

Phase 1: Stabilize Basics (Weeks 1–4)

Pick five schedule-critical assets. Launch operator care checks, define defect triage rules, and start tracking downtime minutes per unit.

Phase 2: Shift To Planned Work (Weeks 5–8)

Build PM plans, institute a weekly planning rhythm, and kit common parts. The goal is fewer “waiting” hours: waiting on parts, approvals, or technician availability.

Phase 3: Remove Chronic Losses (Weeks 9–12)

Run focused improvement events for repeat problems, add quality capability thresholds for spec-critical machines, and tighten administrative workflows so repairs close cleanly.

TPM scorecard

Track weekly on the 5 most schedule-critical assets:

- PM on-time % = PMs completed on time ÷ PMs due

- Planned vs reactive hours = planned labor hours ÷ total maintenance hours

- Breakdowns per 100 hours = breakdown count ÷ (operating hours/100)

- Repeat repairs (30 days) = repeat issues ÷ total repairs

- Downtime minutes = total downtime minutes per unit per week

- Waiting-for-parts hours = hours down while waiting on parts

Weekly review rule: pick one loss, assign one owner, set one due date, confirm it next week.

Common TPM Implementation Challenges and How to Avoid Them

In construction, TPM does not fall apart because the pillars are wrong. It falls apart when the rollout is not run like a jobsite system. These are the five problems that show up most often, and the simple moves that prevent them.

Pushback from the field

If operators feel TPM is “extra work,” checks get skipped and defects stop getting reported. Keep the routine short, train on what to look for, and prove it works with one early win on a schedule critical machine.

Not enough time, people, or downtime windows

If everything is urgent, planned work never wins. Roll out in phases, start with a small set of critical assets, and protect one weekly planning rhythm so PMs and planned repairs actually happen.

Inconsistent skill across operators and technicians

TPM depends on early detection and clean diagnosis. Build skills in small steps: operator signals and reporting discipline, technician troubleshooting and repeat failure elimination. Use OEM procedures as the reference, but standardize how your fleet executes in the field.

Messy data and unclear measurement

If downtime reasons live in texts and memory, you get arguments instead of improvement. Set a baseline, then capture the same basics every time: asset ID, downtime minutes, reason, and what decision was made. Track leading indicators that predict reliability, not just month end totals.

The program fades after the kickoff

TPM dies when it is treated like a campaign. Make it normal work: standard routines, light audits on critical assets, and a weekly scorecard review where one loss gets one owner and one due date. Consistency beats intensity.

Pillar 1: Focused Improvement

Focused Improvement is structured problem-solving to eliminate the few losses that create most of your disruption. It’s the difference between “we fixed it again” and “it stopped happening.”

What It Looks Like on Heavy Equipment

Focused Improvement projects often target recurring patterns such as:

- Cooling package plugging and overheating in dusty conditions.

- Hose failures at repeated chafe points.

- Electrical faults after washdowns or rain.

- Attachment-related downtime (couplers, pins, sensor calibration).

- “Nuisance derates” that create slow running rather than full failure.

Example

An excavator overheats twice a week. The field response is always the same: blow out the radiator, get it back to work, repeat next week. Focused Improvement turns it into a short project:

- Quantify the loss (minutes lost per week, plus knock-on idle time),

- Confirm the chain (dust ingress + inconsistent cleaning + worn seals + operator idle habits),

- Test countermeasures (seal repair, a defined cleaning method at shift end, a deeper clean cadence during peak dust),

- Standardize and audit for 30 days.

The “win” is not the repair; it’s the new standard that prevents recurrence.

Run Focused Improvement like a short PDCA sprint. Start by defining the loss in minutes, trial one countermeasure, convert what works into standard work, and audit it long enough to confirm the problem stays gone. The key is restraint: tackle one equipment class and one recurring issue at a time so results are obvious and repeatable.

KPIs

- Repeat Repair Rate (30 days): Trending down month over month.

- Downtime Minutes For The Target Loss: Weekly total (target: reduce by 50%+ within one quarter for chronic issues).

Pillar 2: Autonomous Maintenance

Autonomous Maintenance puts routine care into operator hands: cleaning, inspection, lubrication checks, minor adjustments, and early abnormality detection. Lean Production’s TPM overview describes this pillar as giving operators responsibility for routine maintenance tasks such as cleaning, lubricating, and inspection.

Most catastrophic failures are not “instant.” They start as small evidence: a fresh seep, heat smell, loose fastener, worn cutting edge, chafing hose sleeve, abnormal vibration. Operators see those signals first, if they know what to look for and if reporting actually triggers action.

Daily Checks That Crews Will Actually Do

The best operator routine is short, visual, and tied to risk:

Excavators

Look for fresh hydraulic seepage at routing points, track tension markers, coupler engagement, bucket tooth wear, unusual swing noise, and belly-pan accumulation that hides leaks.

Dozers

Scan undercarriage condition, track tension, blade/ripper pin health, cooling package cleanliness, and leaks under the belly.

Wheel loaders

Inspect articulation areas, tires, brake response, bucket pin play, and hose chafe points around boom articulation.

Cranes and lifting units

Confirm function checks, outriggers/pads readiness, basic rope/hook visual condition as required by your program, and reinforce wind/ground rules before work starts.

For cranes and lifting equipment, follow your regulatory inspection program and OEM requirements. This guide supports those routines, it does not replace them.

Same-Shift Defect Triage Rule

Every reported defect must receive a disposition the same shift, so operators know reporting leads to action:

- Stop-work: Safety- or damage-critical; remove the unit from service until controlled.

- Plan-and-fix: Schedule the repair within 7 days (or the next planned window, whichever is sooner).

- Monitor: Document the condition and assign a specific recheck date/time.

If reported defects vanish without a visible decision, operator engagement collapses and autonomous maintenance fails.

KPIs

- Daily Check Completion Rate: Target 90%+ on critical assets (those that control your schedule).

- Early Defect Capture: Track the number of defects identified before failure. Expect this to rise at first as visibility improves, then level off as root causes are eliminated.

Pillar 3: Planned Maintenance

Planned Maintenance schedules preventive and predictive work at the right times, with parts and labor prepared. This is where fleets stop gambling.

What “Good” Looks Like For Heavy Equipment

A planned system typically includes:

- Hour-based PM intervals by equipment class (common bands like 250/500/1,000 hours plus annual compliance),

- Seasonal tasks (dust season cooling focus, cold-start checks, winter fluid standards),

- Condition triggers (undercarriage thresholds, oil analysis flags, overheating history, fault-code trends, aftertreatment/regeneration events, temperature/pressure anomalies, high idle %, and repeat derate codes).

Weekly Planning Cadence

Hold a 30–45 minute weekly session with the superintendent (or dispatcher) and the shop lead to:

- Review upcoming PMs and planned repairs

- Confirm parts availability (including kitted items)

- Lock downtime windows around production priorities

- Assign clear scope and technician ownership

This cadence often reduces MTTR because technicians arrive with the right parts and a defined work plan, not guesswork.

These are practical starter targets, not universal industry standards. Adjust them based on your fleet size, utilization, and jobsite conditions.

Starter Benchmarks That Are Realistic

1) PM On-Time Completion

- Goal now: 90% on time

- Goal in 3 months: 95% on time

- “On time” means: you finish the PM before it is more than 10% late.

Example: a 500-hour PM is still “on time” if you complete it by 550 hours.

2) Planned Vs. Reactive Maintenance

- Goal in 6 weeks: More planned work than reactive work

- Goal in 3 months: About 2/3 planned, 1/3 reactive

- “Planned” means: Scheduled ahead of time with parts ready.

- “Reactive” means: Breakdowns and same-day unplanned fixes.

3) Breakdowns

Track: breakdowns per 100 operating hours

- Example: if a machine has 2 breakdowns over 200 hours, that’s 1 breakdown per 100 hours.

4) Repeat Repairs

- Goal in 3 months: 30% fewer repeat issues (same symptom returning within 30 days).

KPIs

- PM compliance = “How many PMs were done on time?” ÷ “How many PMs were due?”

- Breakdowns per 100 hours = “How many breakdowns?” ÷ “Total hours / 100”

Example: 6 breakdowns in 420 hours → 6 ÷ 4.2 = 1.43 per 100 hours

Pillar 4: Quality Maintenance

Quality Maintenance ensures equipment can produce within spec, consistently. It prevents defects by maintaining the conditions required for quality output.

Quality problems rarely feel like downtime until closeout, when everyone is reworking under pressure. TPM pulls quality upstream.

“Quality Conditions” By Asset Class

Instead of vague statements (“grader feels sloppy”), define measurable conditions:

Graders

Blade wear limits, control calibration cadence, steering play thresholds, articulation drift checks.

Excavators

Hydraulic drift thresholds that drive over-excavation, coupler alignment integrity, bucket wear standards.

Rollers/compactors

Verification cadence for amplitude/frequency settings, drum condition, consistent spray/water system behavior where relevant.

Cranes

Inspection and calibration discipline plus lift planning practices that prevent damaged loads and rework.

How To Launch Without Over-Engineering It

Pick your top two rework drivers and ask: what machine conditions must be true to prevent this? Then write:

- A Simple Check,

- A Limit/Threshold,

- A Scheduled Intervention To Restore Capability.

KPIs

- Rework hours tied to equipment condition: target downward trend.

- Pass-count variance vs plan: target reduced variance on spec-critical operations.

Pillar 5: Early Equipment Management

Early Equipment Management (also called Initial Management) prevents reliability problems from being designed into new purchases and rebuilds. JIPM’s TPM award outline references “initial management” as one of the 8 pillar activity areas.

What To Standardize Before You Buy

Fleets win when they reduce one-off complexity:

- Parts commonality (filters, fluids, wear items),

- Access to fault codes and telematics,

- Serviceability (grease points, access panels, cooling package cleaning),

- Attachment compatibility (couplers, buckets, forks),

- Dealer response expectations and warranty clarity.

Commissioning As A Learning Loop

When you buy a new machine, don’t assume it’s “fully settled” on day one. Treat the first 250–500 operating hours as a trial period where you learn what the machine really needs in your environment.

During that period, do three things:

1. Track Early Problems

Write down every fault, leak, sensor issue, overheating event, or unusual wear that shows up in the first few weeks.

2. Collect Operator Feedback

Operators notice what slows them down: hard-to-reach grease points, poor visibility, nuisance alarms, attachment fit issues, or controls that cause extra wear.

3. Adjust Your Maintenance Plan and Setup

Use what you learned to improve the machine’s PM schedule, parts list, and setup standards (for example: change cleaning frequency in dusty work, add a hose-protection step, stock a common sensor, standardize an attachment procedure).

Over time, this approach reduces “new machine surprises” and makes each future purchase easier to maintain because you build a smarter standard every time.

KPIs

- Early-life failure rate: How many problems happen in the first 500 hours of a new unit. Your goal is for this number to go down with each new purchase because you’re learning and improving the setup/standards.

- Unique parts SKUs per asset class: How many different part types you must stock for the same category of machine (for example, excavators). Your goal is to reduce this by standardizing brands/models and using common filters, fluids, sensors, and wear parts.

Pillar 6: Training and Education

Training creates the capability to run the system. TPM expects operators to detect abnormalities and technicians to diagnose efficiently, and both require consistent development.

Construction-Specific Training

Two tracks are usually enough to start:

Operator Track

Daily checks, safe operation habits that reduce wear, early warning signs, and defect reporting discipline.

Technician Track

Hydraulic troubleshooting, electrical diagnostics, OEM procedures, and failure analysis basics (so repeat repairs shrink).

Add a leadership module for foremen/superintendents: triage rules, downtime window planning, and how to enforce standards without fighting production.

KPIs

- First-time fix rate: Out of all repairs, how many are truly fixed in one visit (no comeback for the same issue). You want this number to go up as technicians get better.

- Repeat failures from missed early signals: How often a breakdown happens after there were warning signs that were not spotted or reported (leaks, noises, heat, loose parts). You want this number to go down as operators get better at detecting and reporting issues early.

Pillar 7: Safety, Health, and Environment

SHE is a core TPM pillar because “zero accidents” is part of the TPM intent in many descriptions of the framework.

Many serious incidents start with a maintenance issue. In other words, the machine was already giving warning signs, but the condition wasn’t fixed in time. Common examples include:

- Weak brakes on haul trucks that increase stopping distance

- Hydraulic leaks near hot parts that can lead to fires or burns

- Damaged steps or handholds that cause slips and falls during entry/exit

- Broken lights, alarms, or cameras that reduce awareness on busy sites

- Poor visibility from dirty glass, missing mirrors, or bad wipers

For cranes and lifting equipment, safety also depends on doing the “planning work” every time: confirming the lift plan, checking ground stability for outriggers, following wind limits, inspecting rigging, and keeping people out of the exclusion zone.

KPIs

- Safety defect closure time: How fast you respond to safety-critical issues. For “stop-work” defects, the goal is a decision on the same shift (fix it now, take it out of service, or control the hazard immediately).

- Near-miss reporting quality: Not just how many near-misses get reported, but how useful the reports are (clear description, location, equipment involved, what almost happened, and what was changed). Better-quality reporting usually leads to fewer serious incidents over time.

Pillar 8: Office TPM

Office TPM removes administrative losses that keep assets down: missing parts, slow approvals, unclear work orders, and weak coordination between field and shop. JIPM-related materials include administrative/supervisory functions as one of the pillar activity areas.

Hidden Downtime in Construction

Sometimes the machine isn’t down because the repair is hard. It’s down because the process is slow. A unit can be easy to fix and still sit idle because:

- The work order is missing key details (what happened, where, photos)

- The part isn’t on hand, so everyone waits

- Someone needs to approve the purchase and it takes too long

- Dispatch or the superintendent doesn’t realize the unit is repaired and ready

High-Leverage Fixes

To eliminate this “waiting downtime,” put three basics in place:

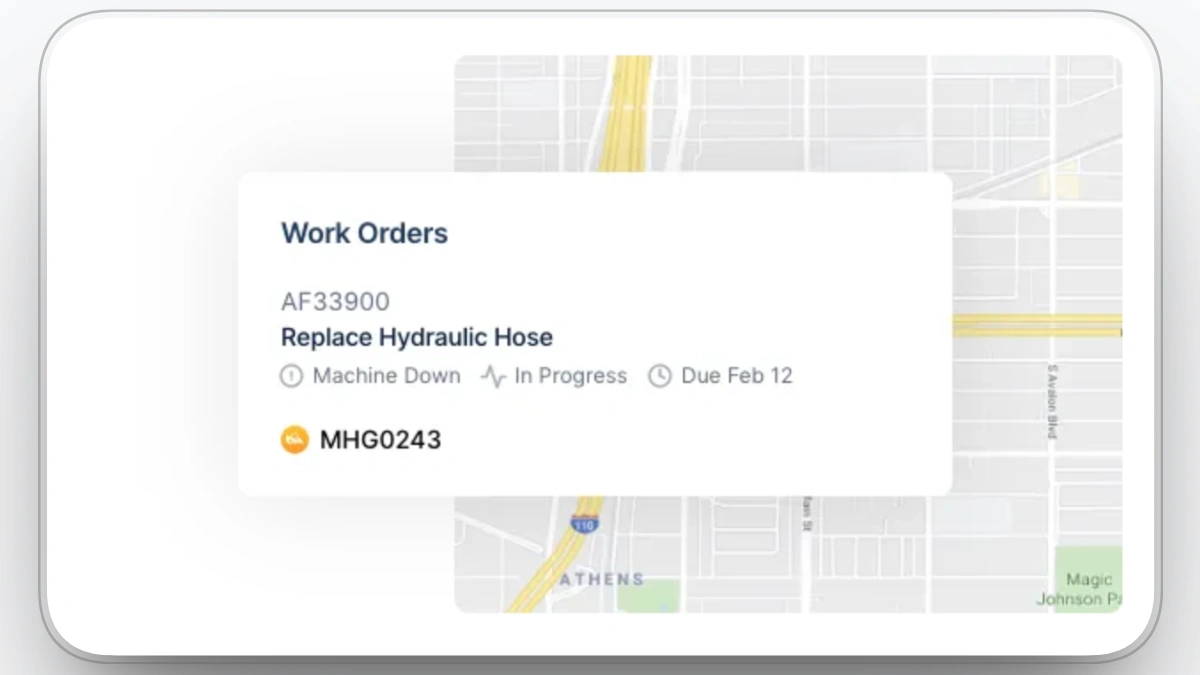

- Standard work orders: Always include the asset ID, symptom, location, priority, and photos.

- Stock the frequent-stoppers: Set reorder points for the parts that commonly shut machines down.

- Weekly planning meeting: Align the shop’s capacity and parts availability with the week’s production plan.

KPIs

- Waiting-for-parts hours: Total time machines sit idle because the needed parts aren’t available. You want this number to go down.

- Wrench time percentage: The share of technician time spent actually repairing/servicing equipment (not waiting, searching, or doing paperwork). You want this number to go up by removing delays and admin friction.

Making TPM Easier to Execute with Clue

Once you’ve defined the TPM routines and KPIs, the next challenge is consistency. In construction, TPM usually breaks down for one reason: the work is happening, but the proof is scattered, paper checklists in trucks, work orders in texts, PM reminders in someone’s head, and downtime notes that never reach the shop.

The goal is simple: make TPM actions easy to do in the field and easy to see in the office. That’s where a fleet management system like Clue can help; not as “extra software,” but as the place your TPM routines live so the scorecard is based on real activity.

Here’s how it supports the pillars you’re already running:

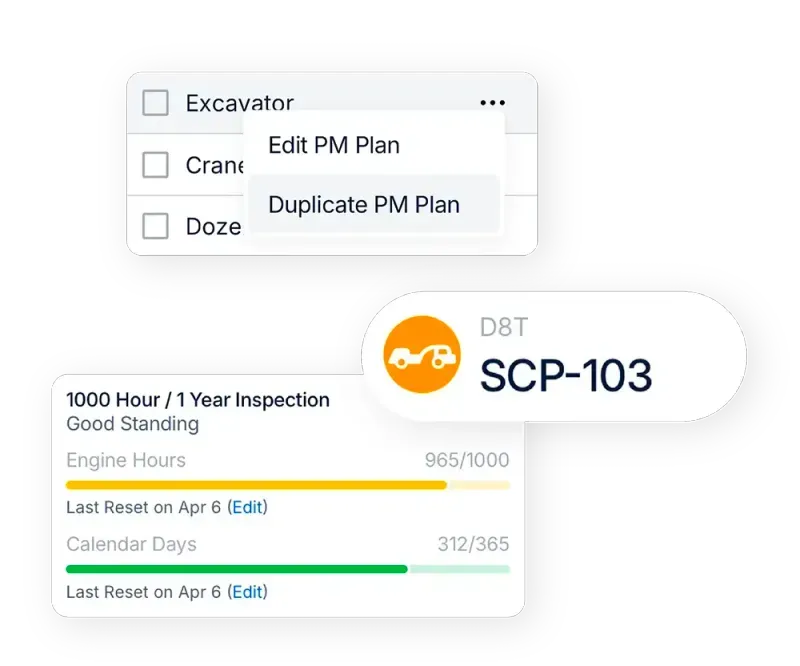

- Autonomous Maintenance: Digital inspections make daily operator checks consistent and trackable, so early defects don’t disappear.

%20Inspections%20Management.webp)

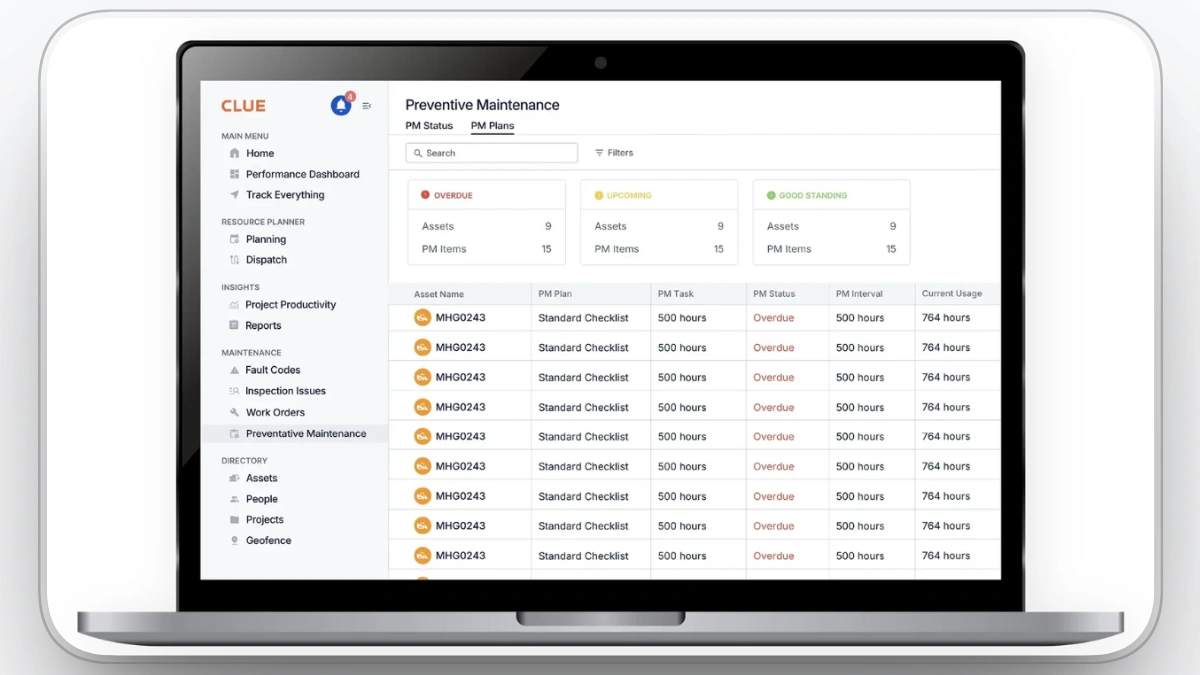

- Planned Maintenance: Preventive maintenance schedules trigger work orders automatically, which reduces “we forgot” maintenance and keeps PM compliance high.

- Focused Improvement: When downtime reasons and repair history are captured in one place, recurring losses become visible and solvable instead of repeating quietly.

- Office TPM: Centralized work orders reduce back-and-forth, improve handoffs, and cut waiting time caused by missing details or unclear priorities.

In other words, the technology supports TPM when it reduces friction: fewer missed checks, fewer undocumented defects, clearer work orders, and better visibility into what is planned versus what is emergency.

Closing

Choose five critical machines. Launch operator checks, build PM plans, and run one focused improvement event on the most painful repeat problem. Review the scorecard weekly. Within a month, you should see fewer start-of-shift surprises. Within a quarter, you should see planned work overtake reactive work on the assets that control your schedule.

That is the practical promise of the 8 TPM Pillars: a steadier fleet, a steadier jobsite, and far fewer days lost to avoidable chaos.

FAQs

What’s the difference between Autonomous Maintenance and Planned Maintenance in the 8 TPM Pillars?

Autonomous Maintenance is the operator-led layer (clean, inspect, tighten, basic checks) designed to catch abnormalities early, while Planned Maintenance is the maintenance-team-led layer that schedules PMs, repairs, and condition-based tasks so work is done deliberately instead of reactively.

Is TPM basically the same thing as preventive maintenance?

No. Preventive maintenance is one component inside TPM. TPM is broader because it combines PM with operator-owned maintenance, focused improvement (kaizen), quality-focused controls, training, safety, and administrative process improvements, so reliability becomes an organization-wide system, not just a maintenance calendar.

TPM vs RCM for heavy equipment fleets, when do you use which?

TPM is the operating model that builds daily discipline and shared ownership across the whole fleet. RCM is a deeper analysis method used to choose the “right” maintenance tasks based on failure modes, consequences, and cost, often best reserved for high-criticality assets (e.g., cranes, specialty rigs, mission-critical production spreads).

Transform Your Equipment Management

.webp)

%20Meaning%20in%20Construction.webp)